Amarna: Ancient Avant-Garde

- Marjorie Vernelle

- Jun 1, 2019

- 5 min read

Updated: May 7, 2021

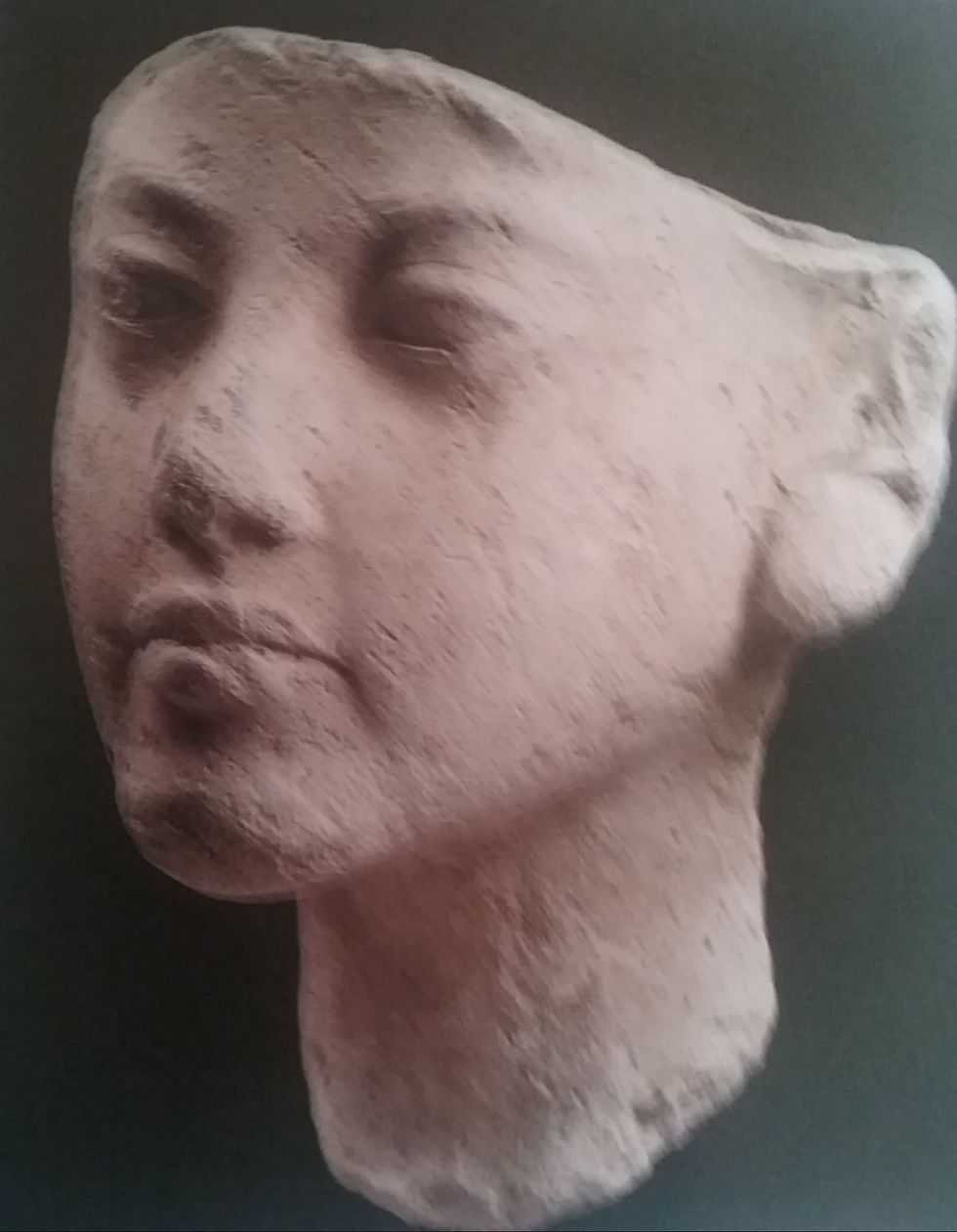

I first saw this face at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art show, Pharaohs of the Sun. I stood for a long time looking into this half-finished head of pharaoh Akhenaten. This was a normal version, by which I mean normally proportioned features (yes, they exist). This handsome face with rounded nose and full lips reminded me of my cousin Bobby, also an artist with an unique vision. That made Akhenaten seem closer to me in time than 3,300 years. The statue's eyes were marked in but only with a hint of where the pupils would be. It made me long to fill-in the missing detail, as if that might tell me the great secret of his kingdom: What he meant to communicate with his art.

My looking with awe into the face of a pharaoh started when young, around the age of nine, when my mom took me to the Joslyn Art Museum in Omaha, where my family lived. We'd arrived early for a recital, so mom walked me through some of the exhibits. I remember turning a corner into a rather dimly lit area. I felt compelled to look up to my right, where upon the top of a partial wall, used to divide this exhibit into its own special space, was a bust in black stone of a majestic looking man, Pharaoh Amenhotep III (1386-1349 B.C.). The bust was done in classic pharaonic style, with even features, square jaw, and pupil-less eyes looking into forever. Though I was also impressed by the beautiful golden objects in the display cases, I would periodically look up at the bust of that pharaoh, wondering how anyone could be so magnificently perfect.

Of course, perfection is an ideal, and ideals change. Therefore, representations of those ideals change also. From Amenhotep III to his second son, Amenhotep IV (a.k.a. Akhenaten), there was a radical change in the concept of the ideal vision of the world (see images of father and son above). From many gods to one, from powerful priests to one priest, pharaoh himself, everything changed. When change of that sort occurs, art is put in service to the new ideal. In the Amarna period, this change was radical. Not only do we see the pharaoh and his queen in intimate scenes with their children, we also see Akhenaten and Nefertiti represented as equals, even with scenes of the queen smiting enemies like a warrior ruler. We see pharaoh represented not in idealized masculinity like the bust of Amenhotep III that was imprinted on my 9-year-old mind, but in a sort of gender-bending form with sagging belly, wide hips, narrow chest, thin arms and legs and that oddly beautiful, distorted face. But why?

Once the actual remains of Akhenaten were genetically identified, the scans of his head did not reveal any particular distortion, though there are questions about whether he suffered from Marfan Syndrome, which elongates parts of the body. However, the extreme distortions in the sculpture and other images seem to be trying to tell us something. But what? When I look at this from an artist's point of view, I see communication of a new ideal. For instance, the ancient worlds of the Greeks and Romans focused on representing the physical body. With the coming of Christianity, art changed toward minimalist figures as we see here in the Four Tetrarchs (300 A.D.), taken from Constantinople and now found in Venice.

This art served a new religion that was focused no longer on the body, but on the spirit. Why represent that which is here today and gone tomorrow? After all the souls of good Christians were promised life everlasting - after the death of the body. It was not that the artists who had made beautiful life-like works had forgotten how to do that. There are always artists capable of rendering the human image realistically. The main thing is whether society calls upon them to do it.

In the Amarna period artists were called upon to create that which went with the new religion. We see a sharp break with what had been and a move to what was new, unusual, different, and disturbing, or what we now call avant-garde. This is art that shakes things up and scares those who are holding on to what has been. In our day, the representations of Akhenaten would be called "gender fluid." His close companionship with Nefertiti as partners in this great experiment with reshaping the consciousness of a whole society is shown repeatedly. It is now even thought that when her name disappears in the 12th year of his reign, it is not because she died. No, she may have become an entity known as Neferneferuaten, another channel through which the Aten could be worshipped.

Whatever their grand dreams were (immortality, perhaps?), life and time caught up to them. Nefertiti's name has been found in recent years listed as the Queen in year 16 of Akhenaten's reign, and swabtis (statuettes of servents), of the quickly fashioned kind made after one dies, have been found with her name on them and marked with year 16 of the pharaoh's reign. Ahkenaten, himself, died in year 17, leaving much of his religion a mystery, something that was too far ahead of his people.

When that happens, as it did centuries later during the 16th century in Europe, when Mannerism, with its hard to decipher symbolism, moved so far ahead that we would not see the likes of it again until the art of the late 19th century, society pulls back to what was known. So, too, did the art of Ancient Egypt return to the norms of its codified classical style, as can be seen in the statues of Rameses II in Abu Simbel, done some 100 years after Akhenaten. Suddenly there were no more of the wonderful naturalistic pieces like these below of Nefertiti and one of the Amarna princesses.

Whatever it was that Akhenaten wanted to show about gender equality, the joys of his family life, and the presence of love, coming in the form of the sun's rays with little hands at the end of each beam of sunlight, those images were no longer the ideal. The culture pulled back to what had been its norm, leaving us with just suppositions about what exactly Akhenaten's art meant or was intended to do. The answers to that conundrum blow in the dusts that shroud the remains of the heretic pharaoh's capital, Amarna, just whispers in the sand.

What is your fondest memory of something Ancient Egyptian? Log in and tell us about it.

To see the fabulous jewelry done in Egypt and Nubia in ancient times go to Women of Egypt Magazine https://womenofegyptmag.com/2019/05/20/11-pieces-of-jewelry-from-ancient-egypt/

This is a must see: Reconstructions of Ancient Egyptian Royal Faces. Go to YouTube, Faces of Egypt posted by Jude Maris to see M.A. Ludwig's photo-shopped versions of Akhenaten and Nefertiti, along with those of other royals: https://www.youtube.com/results?search_query=faces+of+egypt+by+m.a.+ludwig

Image of Four Tetrarchs from Wikimedia.org used in accordance with Fair Use Policy.

Photos of Egyptian artifacts taken by me from the Pharaohs of the Sun catalog and used here for informational purposes according to Fair Use Policy.

For more on Marjorie Vernelle, see the author page at amazon.com/author/marjorievernelle

She also has an engaging art history blog that talks of painting and wine on ofartandwine.com

© Marjorie Vernelle 2019

Thanks. I always find it interesting when a culture breaks its own mold and strikes out toward something new.

I've never even thought about this most interesting subject. All of your articles are so well done and thought provoking. Thank you!